Travels In Qinghai Province

We are leaving town early, on the advice of the driver who is anxious the road ahead may be bad. It is a beautiful morning, the sun just creeping over the valley walls. We boiled water and milk, ate bland fried bread, and left the hotel smoothly. The shops haven’t opened yet, though the street sweepers are out in force and workers, Muslim, Tibetan and Chinese all head to work diligently. We glide through town in the morning chill, to the sad whine of Chinese love songs. As we pass the monastery the lines of dharma wheels are already being spun by the devotees. The gold roofs and exquisite coloured temples exude a magic that is such an essential ingredient to the allure of Tibetan Buddhism.

We pass under the ornate city gate and face a huge valley that meanders into the dark distance. Clouds seem to boil over the ridge line at the valley head and the sun catches the tops of the western flank. A rushing muddy river inevitably dominates the valley floor, the Naga spirit that has ruled this land from the out set. The road finds it’s way along the river, at times clinging to a shingle ledge, then crossing over dusty concrete bridges, at other times sharing the valley floor with the ripe fields of wheat and oil seed. The smooth road surface quickly fades and our old VW Santana starts to feel the weight of four men and baggage on a rocky road.

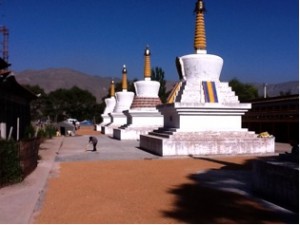

My traveling companions, Bing Bing, his Father and his father’s friend the Muslim driver and I are enjoying a shared excitement and anticipation. None of us having taken this road before and it was only after some debate the driver agreed to take it….as long as we get an early start because we will be driving slowly. He was right, aside from small sections of pitch we drive along a tattered rag of a road that the river and rain have been kind enough to leave us. The open valley is dotted with pylons and the occasional huge stupa and poles of fluttering prayer flags . The tree-less hills, give their soil to the Naga, delivered down raw ravines. Where efforts have been made to plant lines of horizontal grass or rice, and wheat terraces have been cut, the erosion is seemingly controlled for now. But this is certainly one of the biggest environmental problems of this region. You can tell there used to be trees all over these hills, but the human beings have consumed them and, for now, out-live them.

Soon the valley walls start to close in and the steep sides cling onto a few trees that man cannot yet reach. The Chinese government, in their hubristic determination, have decided the high valley ahead of us is flat enough to make an airport, I can’t imagine what for, but this has in it’s turn necessitated a better road, so now and again between the goat herds, mud walled Tibetan villages and small country monasteries, we pass grand-scale construction-worker camps. Steel, concrete, heavy equipment and their slaves (or masters) live in muddy sites littered with garbage, tied steel, forming-lumber and green tents. The workers all wear florescent jackets, hard hats and hardened faces…both men and women all far from home. They are the mobile worker units that front the onward drive of China’s internal expansion.

Our rushing river is reducing to a stream, trees are more commonplace now. It is still cold on the valley floor. I keep the window open to let out the drivers constant cigarette smoke. Soon we are climbing , the mud causing the wheels to spin….I have been here before. Memories of our trip through the mountains of Romania flicker in my mind’s eye. The landscape is actually very similar, complete with road construction and high passes. Only the stupas on the hills exuding prayers of harmony, mark any difference at this point. We are now behind trucks on a long snake of switchbacks that carry us higher and higher on their slippery muddy track. It is amazing how all over the world trucks laden with the loads of human needs gather at mountain passes. Supplies for the spreading of the masses…..what is it that presses us to move into these high places? The tree line is below us now, rock and grassy mountains above us still, and in the gaps between them, brown peaks dusted with snow. The pass is marked by tattered prayer flags and what at first sight might seem like litter every where, but is in fact the scattered remains of the paper money and prayers thrown in reverence to the spirits in thanks for the safe passage.

From the pass the road descends towards the open plains.

After watching Hi-macs dredge gravel out of what was once an idyllic meandering river, we enter a new settlement under construction. The huge Chinese sign outside the town proclaiming with no little irony: “We must protect the environment for the people and the country”. As we pass through the street of mud that makes the main road, the true wild west nature of this Chinese expansion into the Tibetan plateau is revealed. Piles of bricks line the mud, behind them concrete mixers, cranes and construction crews create a new world order to ensnare the nomadic people into civilized life. Those Tibetans that have not succumbed to the policy of rural depopulation come to town on motorbikes (only a few on horses) to load up with supplies and trade balls of Yak butter for plastic sacks of food and feed. Their incredible, rugged, deep faces are weathered yet smiling reflections of the wide open spaces. The men with long wild hair, Apache style , dressed in black suit-tops, leather jackets or traditional gowns with long sleeves to cover the left hand and on the other side the arm and shoulder is uncovered. I am not quit sure why, but I suspect it might be to have a freer arm for horse handling or sword wielding maybe? The elder women are often bent forward from a life of toil, they wear their traditional thick skirts and silk lined tops, their heads are either wrapped in a bundle of ragged scarves or they have long ponytail plats, often tied together at the bottom of the their back. The high mountain life does wonders for the preservation of their beauty. The young women glow with flush red cheeks and irresistible smiles, often in traditional cloths, but equally beautiful in a pair of rough old black jeans. They are the height of ragga cool.

We have reached the grasslands, a massive wide open ocean of seemingly infinite pasture, bordered in places by distant hills. Here are the scattered nomad tents and their herds of yaks and sheep dotted like sails into the distance, away from the rattling road lined with telegraph poles we are trundling along. It is very cold, even at midday and I am glad for my Chinese railway workers coat. We are at 3500 meters … only 200 meters lower than Lhasa, and although the land is flat and seemingly easy, small exertions like walking up to a roadside stupa, takes your breath away. It is wise to spend a few days here to acclimatize your lungs, and equalize the pressure one feels in your head. I wish I had more time to roam around here. It had been part of my plan to try and link up with these people, but the scale of the space and the distances have suddenly dawned on me. To leave the comforts of my car and Chinese companions at this point would be foolhardy, I think. I need a Tibetan friend to get inside the system here. I can only say that this has given me a small taste of what I would love to experience more completely one day…a trip to higher-inner Tibet. The Chinese seem to live in mocking fear of these alien people, yet their dominant ways give them total control. It’s such a familiar tale of a technologically superior race overriding the deeply spiritual and nature-immersed inhabitants.

Mr Shu,a kind hearted government man and friend of Bing Bing’s mother is a leader of the economic development division in Tong ren, with whom we had dined on our first night, explained the current policy in it’s simplest and most shocking terms. The government sees the best way to protect the environment for the future, is to build mini-cities in these remote regions and to then take the farmers and nomads off the land and allow it time to recuperate. Mr Shu was keen to show me tree planting projects and erosion control measures that exemplify this policy. The local food supply, he says, will then be boosted by a surge of hi- tech farming, that will require less manpower.(Echoes of Omars green houses coming in here!) What cannot be grown locally will be delivered to these regions by the new highways that are being built in all directions.

What are the farmers to do living in the towns and cities you might ask? They will run shops and business or become workers. The extent of this megalomaniacal growth knows no bounds it seems. The compound housing in some areas could easily be mistaken for concentration camps, except each brick unit has a small yard to grow your own food. In some areas we passed huge acres of land laid out with these housing projects. Most of them empty or still being worked on. As well as the accommodation, they also build lines of shop units, all the same with roll down shutters along the road side. It is very shocking to see how this simplistic Maoist plan is being brutally put into bricks and mortar. Bing Bing’s Dad surprised me with his comment: “There are only two places in the world that can get away with building houses like these, China and North Korea”.

Sadly the road started to take us down from the green wet plains and we began our descent to lower plains, equally as vast and stretching off to massive mountains in the distance. We stopped for lunch in a dusty town called Tong den. It was tucked down low in a valley that cut through the plain. We were back in mixed Muslim and Buddhist communities now. We ate at a Muslim restaurant…all four of us huddled over plates of noodles, veg and lamb, slurping it up with our chopsticks. Table manners, as Zanti and Ceiba know them (!), are not a high priority here, it’s just slurp and go. The public toilets of Tong den, took the prize for being the most disgusting experienced so far…why with all this construction and technology do the Chinese always seem to overlook the basics?

After lunch we continued along this lower level grassland plain. The landscape became dryer , but still green, until at one point, a golden streak of pure sand appeared off to our left. It then grew and became a line of clearly visible sand-dunes. As if alive, this dragon-like desertification followed us over the next mountain pass and took possession of the whole left wall of the next valley. You could see government attempts to plant line of trees, to stop the monster, but it was clearly a futile effort and the sand poured over the ridge line and was beginning to make it’s way to the river that we drove along. The herds of long horned sheep and goats we passed looked very guilty of being at least partially responsible for this unstoppable march of the desert. On the right hand side of the valley the overgrazed grass struggled to keep a grip amidst gullies and crumbling ravines. The occasional villages we passed through were all made of rammed mud, high protective walls with small windows. The whole appearance was very much like the foot hills to the Atlas mountains in Morocco. Soon the road delivered us to a wide open valley with groves of trees. The surrounding desert mountains glowing as the evening sun caught them, contrasting beautifully against the dark dusty trees. We came into the town of Gui de on the banks of the Yellow River. Gui de was once an ancient walled city from the 1300’s. It has long since burst the eroded city walls and moat which now lie at the heart of a mixed-up concrete communist mess, but still has districts of rammed mud walls set out in a maze.

I had decided to stay here the night, instead of going back to the big city of Xining with my companions. Bing Bing was very kind, and concerned for my well-being, so helped me find a cheap government hotel were I checked in and said good-bye to my companions, until I see them on Sunday back in Xining.